Basic theory knowledge pt 2: on Guitar!

Let’s now go back to the basic theory post (quite successful over 10k views just the day I posted!) , and let’s see how things apply to guitar…just read the explanatins in red and watch the videos!

Let’s start again:

The natural sounds are:

|

English |

|

C |

|

D |

|

E |

|

F |

|

G |

|

A |

|

B |

You might also find in some books the name of these notes in Italian (nothing to do with ‘solfege’!) Do,Re,Mi,Fa,Sol,La,Si and in German C,D,E,F,G,A,H.

Sharps and flats.

# = sharp: raises the given note of a half step.

One half-step on guitar is a fret, easy. When you move up a fret (from the headstock to the body of the guitar) you are playing two notes that are a semitone/half-step apart from each other. From G natural to G# you would move up one fret.

## = double sharp: raises the given note of two half steps (also noted ‘x’).

From G natural to G## you would move up two frets.

b = flat: lowers the given note of a half step.

From G natural to Gb you would move down one fret.

bb = double flat: lowers the given note of two half steps.

From G natural to Gbb you would move down two frets.

= natural: cancels sharps and flats (double natural cancels double sharps and flats).

The Chromatic scale.

In this first video I start from the chromatic scale and show you how to build a major scale:

The chromatic scale contains all 12 natural and altered sound (using sharps and flats).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| C | C#/Db | D | D#/Eb | E | F | F#/Gb | G | G#/Ab | A | A#/Bb | B |

Notes called with a different name, but identifying the same sound, are called enharmonic (i.e.: C# e Db). The shortest distance between two sound of the chromatic scale is a Half Step, the distance of a fret on the guitar.

Intervals.

An interval is the distance between two notes.

Intervals of a second, third, sixths and seventh are called major. If a major interval is raised by an half step it is calledaugmented. If a major interval is lowered by an half step it is called minor. If lowered by two half steps, diminuished.

Intervals of a fourth, fifth and octave are called perfect. If a perfect interval is raised by an half step it is calledaugmented. If a perfect interval is lowered by an half step it is called diminuished (note the difference).

All the intervals from the tonic of a major scale to any other note of tha scale are major or perfect (i.e. between C and D=major 2nd, C e E=major 3rd, C e F=perfect 4th, and so on…)

Intervals can also be calculated summing up half steps: one half-step on guitar is a fret, easy. When you move a fret up (from the headstock to the body of the guitar) you are playing two notes that are a semitone/half-step apart from each other.

|

N.of htps |

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| Interval | m2 | M2 |

m3 |

M3 |

P4 |

4aug |

5dim |

P5 |

5aug |

m6 |

M6 |

6aug |

m7 |

M7 |

P8 |

where m=minor, M=major, P=perfect, dim=diminuished, aug=augmented.

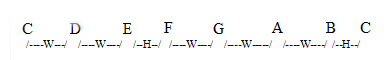

How to build a major scale.

Read the theory and watch the video below:

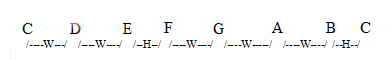

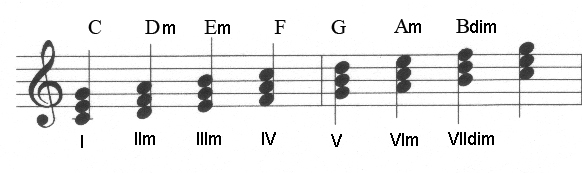

The spacing of the notes in a major scales follow this rule:

WWHWWWH

Where W = Whole step (a major second) H= Half step

Example : C major

To build major sales in other keys use exclusively either sharps or flats choosing the notes so that a note with the same name is never repeated. In doing so you will only use Diatonic half steps (given by two notes with different name, i.e. C-Db, opposite to Chromatic half steps given by two notes with the same name, as in D –D#).

ON GUITAR:

Major scale – fixed position patterns

The Major scale template above is from TrueGuitarist.com’s ‘The Guitar Kit’, a free collection of guitar templates.

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD ‘THE GUITAR KIT’ FOR ALL THE SCALES AND TEMPLATES YOU’LL EVER NEED!!

This is a list of all the major scales in all keys. The order follows the amount of sharps and flats in the key.

Keys with flats.

| C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

| F |

G |

A |

Bb |

C |

D |

E |

| Bb |

C |

D |

Eb |

F |

G |

A |

| Eb | F | G |

Ab |

Bb |

C |

D |

|

Ab |

Bb |

C |

Db | Eb |

F |

G |

|

Db |

Eb | F |

Gb |

Ab |

Bb |

C |

|

Gb |

Ab |

Bb |

Cb |

Db |

Eb |

F |

|

Cb |

Db |

Eb |

Fb |

Gb |

Ab | Bb |

Keys with sharps.

| C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

|

G |

A | B | C | D | E | F# |

|

D |

E | F# | G | A | B | C# |

|

A |

B | C# | D | E | F# | G# |

| E | F# | G# | A | B | C# | D# |

| B | C# | D# | E | F# | G# | A# |

| F# | G# |

A# |

B | C# | D# | E# |

| C# | D# | E# | F# | G# |

A# |

B# |

Relative minor (key)

Every major key has one relative minor which is made of the same notes, but starting from the sixth note. In other words, starting a minor third below (or a major sixth above) the root of the major scale. For example if we take C major its relative minor is A minor, spelled A B C D E F G.

On guitar: To play the relative minor, just start two notes before the note in the red circle.

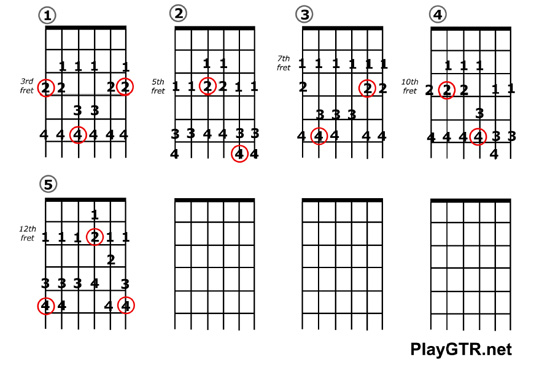

Circle of fifths.

The circle of fifths one of the most used ways to summarize all I explained so far. It is very useful to memorize how many and which alterations a specific key has.

I find very useful to memorize FCGDAEB and the same sequence backwards BEADGCF. The first is the order of sharps the second, of flats. So if a key has, for example, 3 sharps (A major) they will be the first 3 notes in the first seqence (F# C# G#).

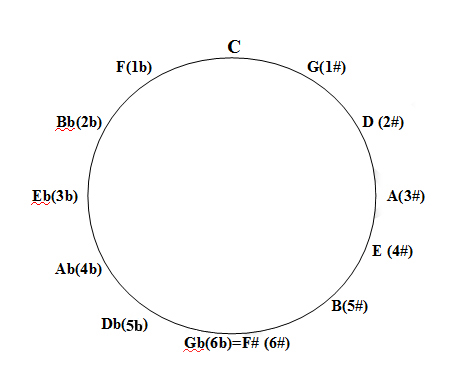

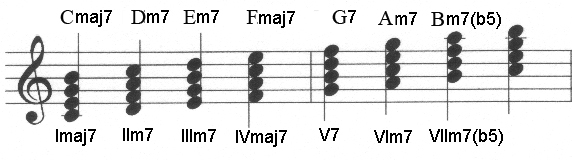

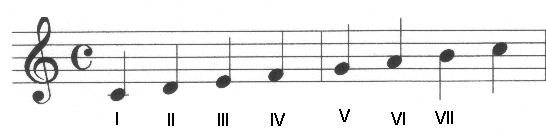

Harmonized major scale – How to build chords.

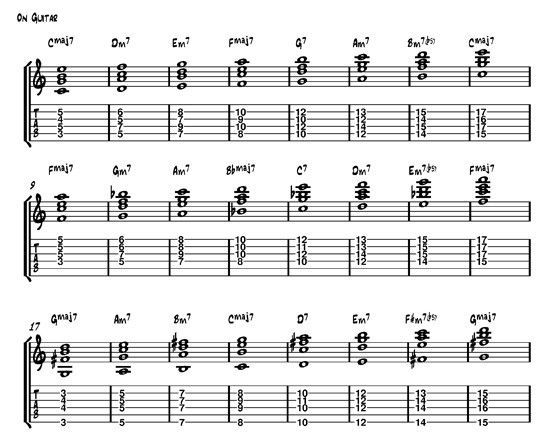

A practical application on guitar:

In the example below every note of a major scale identifies a ‘degree’ of the scale. In the example I have used C major, but this is valid for every other major scale in any key.

If I stack on every degree two more notes a diatonic third apart (basically every other one) I end up with different kinds of triads (triad=group of three notes). These triads are shown in the example below. If we analyse the intervals between notes:

a Major Triad has a Maj 3rd and a Perf 5th (Eg. C-E-G: C-E=maj 3rd , C-G Perf 5th).

a Minor Triad has a min 3rd and a Perf 5th.

a Diminuished Triad has a min 3rd and a diminuished 5th.

You will have the same series of chords in all the other keys Eg: F major: F, Gm, Am, Bb, C, Dm, Em.

Already with this knowledge we can understand how to Analyze simple songs or how to write pop songs:

If we stack another note a diatonic third apart from the last note of the above triads we will have Seventh chords.

This again is valid for all the 12 keys. This concept is vital to understand how songs are built and how to pick the correct scale for a solo.

On Guitar this note choice for 7th chords might not work…let’s see some more popular choices to play this on guitar:

With this we can now analyse more complex songs like a simple jazz standard…watch the video:

I hope you enjoyed this lesson!